There is a lot of rain in the eerie, gripping new film "Take Shelter". Not just rain, but downpours with portentious, threatening thunder, terrifying storms with menacing, rolling dark clouds and tornadoes. Sometimes the rain falls in thick, golden droplets, like motor oil. Curtis, the troubled working-class family-man played by Michael Shannon, might be having apocalyptic premonitions. Or, as he fears, he may be falling victim to hereditary paranoid schizophrenia.

Either way, his horrific visions are playing havoc with his personality. He can't sleep for the terrifying nightmares: monstrous people are trying to take his family away; the family dog turns on him viciously; a plague of dying birds rains from the sky. He is trapped inside his fears, those deep within his psyche, and the ones inherent in his family responsibilities.

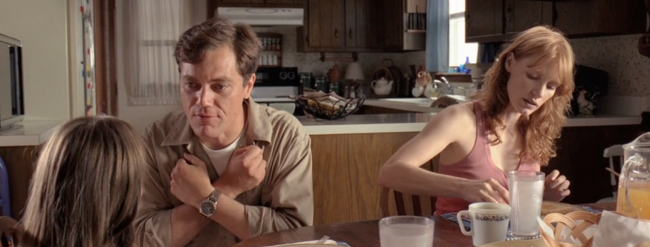

Curtis' perceptive wife Samantha (Jessica Chastain) notices changes in Curtis, unusual things. His behavior and his appearance of illness become gradually more erratic, more alarming. Their little girl Hannah, a special needs child with hearing loss, needs an implant and special schooling. Curtis can't afford to become distracted at his job on a utilities crew, as his employee insurance plan is crucial to their daughter's care.

The rural, god-fearing, Lions-Club world in which Curtis belongs discourages men from revealing weakness or confiding in a loving spouse or close friends. For much of "Take Shelter", we wait in dread for the situation to become so dire that Curtis must either tell someone what is happening within him, or explode. In this film, both things happen.

"Take Shelter" does not want to comfort us with easy solutions to the terrifying plight of mental illness; nor does it want to follow a path toward a typical supernatural horror story. In fact, we are never quite sure what kind of film it actually will turn out to be, which intensifies a feeling of mounting anxiety and tension. The schizophrenic nature of the film, where there are no safe harbors, is an effective way to depict Curtis' psyche, and manipulate our responses in a way similar to what audiences must have felt about Mia Farrow in "Rosemary's Baby": was she losing her mind, or was something sinister really occurring?

The film means to unsettle, and disquiet us. Writer/Director Jeff Nichols (who won a Director's Week Grand Prize at Cannes) walks a delicate tightrope here. We are not certain if this film represents the fevered and terrifying vision of a madman trapped in a life of quiet desperation; or if it is actually a supernatural thriller in which Curtis is a prophet of an apocalyptic future. The film needs to keep this difficult balance, or it would easily tip into the realm of absurdity (which it comes perilously close to once or twice).

I must stop for a moment and heap some praise on the two leads. Like many new films where the acting has overcome difficult material, the fine performances in this film elevate "Take Shelter" into the ranks of serious, thoughtful filmmaking.

Michael Shannon, who can make a good career from playing seemingly normal but very unbalanced individuals, slowly pulls out all the stops. He holds himself in check, as his character feels extreme duress and pain, the way I have seen blue-collar guys do. Then, he unleashes his anger and fear, in a well-acted (if slackly directed) scene at a community dinner. He is a powerhouse, appearing in almost every scene, at turns creepy and heartbreaking. He is terrific.

Jessica Chastain's Samantha is a meatier version of her saintly mother in "Tree of Life", which almost seemed like a wordless dress rehearsal for this role. Chastain is so direct, so fresh in her scenes, her emotions so well controlled and her delivery so natural, that I believed every minute she was on the screen.

Nichols has good control of his camera and visual effects, and startling use of sound. His screenplay builds incident upon incident to a claustrophobic and terrifying climax, in a style less graphic but as suffocating and suspenseful as "The Exorcist". He keeps the action grounded in a stark, everyday existence, which makes Curtis' transformation even more unbearable once he succumbs to mood swings, night sweats, vomiting, bloody seizures, and obsessive behavior.

The backyard storm shelter that Curtis builds out and fortifies, which imperils his job and his friendships and drives his wife into a rage, can be seen as a metaphor, for his entrapment, or for an escape from a world that shows signs of becoming threatening and overwhelming.

In fact, the film dabbles in lots of metaphors: First, the motor-oil rain could be a symbol of environmental disaster, leading Curtis to nightmares of extreme, damaging climate change. Second, making Curtis a reticent Everyman can be seen as a statement against a culture in which men are emasculated for admitting the need for help. Third, the nightmare visions could be seen as a world become completely hostile, where one can take no comfort even in the safety of one's family, even a loyal dog. Finally, the real storm that brings the family to the shelter leads to a scene that could be a microcosm for Curtis' life, and helps us understand the "being afraid" that Curtis tries to explain to Samantha.

(Of course, Nichols may have had none of these metaphors in mind from script to screen, but I still don't suppose he wanted anyone to take away any literal interpretations; if so, he miscalculated his final scene.)

The climactic sequence in the storm shelter had me very afraid. By this point I could not be sure if they wouldn't be trapped there for good, or if they would somehow emerge. I actually felt like I was going to suffocate. All of the elements of the film came together in what might be the most purely suspenseful movie sequence of the year.

I would have been happy to see "Take Shelter" end on a quiet note right after this horrific sequence inside the storm shelter. However, what follows is that final scene, one that will have people shaking their heads in confusion. It defies logic, is even facile, but after some thought, I accepted it as a final nightmare image where Curtis is embraced, not threatened, by those around him; in other words, a turning point for the better. I fear, though, that many viewers will feel betrayed by this ending, and conclude that "Take Shelter" was nothing more than a simple vision of the apocalypse.

Given the dual nature of the entire film, who is to say which interpretation is the "real" one?

(Note: This review was especially difficult to write. Mental illness hits close to home, and while I would not expect any film to lend me all of the insight I need in order to help a loved one, I must say that "Take Shelter", for me at least, did not finally exploit "madness" for the sake of cheap horror. For that, I was grateful.)

Great review. Your final note is right on the mark.

ReplyDelete