Before I tackle some of the more interesting categories, here's a brief summary of some of the trends I noticed in the movies of that year...

The treatment of sexual themes and violent content was still not (for the most part) a no-holds-barred proposition, which meant that the introduction of explicit nudity, sexuality, or violence had to be approached in a context of quality in order to be acceptable---usually.

Just about any important film you could name in 1970 took cinema a little bit further, either thematically or by a memorable or controversial scene. Political themes, too, were plentiful. Reading the marquees of theaters in a big city was like a social network of sorts...you could share your political affiliation with others at a screening of a particular film, often for repeat viewings. (Remember, there was no home video then, and no multiplex theaters.) Lots of movies appealed to the activism prevalent in young moviegoers. It seemed that certain films could actually change the world, and people of a certain idealistic worldview tended to align with each other through these films.

Or you could champion a new look or style or cinematic groundbreaker.

An "important" movie of that era was often known as being the first one to try something new, or one with "that must-see scene", or one that called the Establishment to question. Many were Oscar hopefuls, but not all.

"Women In Love" had the infamous nude wrestling scene between Oliver Reed and Alan Bates. It would also prove to feature the first performance by an actress (Glenda Jackson) who played a nude scene to win an Oscar.

"The Boys in the Band" was an unabashed story about homosexuals; and Liza Minneli's follow-up movie after her first Oscar nomination (see "the Sterile Cuckoo") featured a (horribly stereotyped) gay character in "Tell Me That You Love Me, Junie Moon."

The historic mistreatment of Native Americans drove films like "Little Big Man", "Soldier Blue" and "A Man Called Horse". The first two featured bloody scenes of slaughter that were obvious parallels to the My Lai massacre (viewers were outraged by the brutality in "Soldier Blue"); the latter became notorious for an initiation rite featuring Richard Harris' pectorals and two chicken claws.

The otherwise sentimental "Love Story" broached the uncomfortable subject of young adults rejecting religion, and startled viewers with the heroine's brash dialogue. "Patton" was well-known for it's profanity (so mild today it might pass completely unnoticed). "M*A*S*H" was even more profane, and forced viewers to look at battlefield bloodshed even as they were convulsed with laughter...it was anarchic, it was a party, and nothing like it had been seen before.

Mike Nichols directed an all-star cast (Alan Arkin, Tony Perkins, Jon Voight, Art Garfunkel, Orson Welles, among others) in the film of the classic anti-war novel "Catch-22". It should have appealed to the same crowd as "M*A*S*H" but somehow its clunky cynicism and heaviness (and the explicit treatment of the book's horrifying Snowden sequence) turned off audiences.

"The Revolutionary" (Jon Voight again), "The Strawberry Statement" (with "True Grit"s Kim Darby), and Michaelangelo Antonioni's "Zabriskie Point" functioned as a rallying cry for youthful alienation and activism started by "Easy Rider" the previous year. While none of these proved very popular, Antonioni's film in particular was widely dismissed and misunderstood even by those who loved "Blow-Up" in 1966 (although I really enjoyed it's originality, its beauty, its music, and its vision of an aridly commercial society).

The burgeoning urban film, or "blackxploitation film", which stereotyped the criminal culture of the inner city, got its start in 1970 with the fairly well-made "Cotton Comes to Harlem", reaching an apex of sorts the next year with "Shaft". Civil Rights and more sensitive treatment of race relations could be found in pictures such as "The Landlord" and "The Great White Hope".

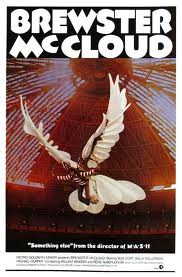

Best Director Nominees Arthur Hiller ("Love Story") and Robert Altman ("M*A*S*H") both made lesser films of varying success in 1970: Hiller added his own venom to New York City in "The Out-of Towners", a raucous, popular but critically lambasted comedy starring Jack Lemmon and Sandy Dennis; Altman made the far more quirky and interesting "Brewster McCloud", starring a pre-"Harold and Maude" Bud Cort on a flying contraption in the Houston Astrodome. Audiences ignored it.

"Joe", very dated now, but one of my favorite films of 1970 or any other year, was directed by former soft-core porn-filmmaker John Avildsen ("Rocky") and starred Peter Boyle (the "Young Frankenstein" monster) and Susan Sarandon, (in her film debut) portraying, respectively, a bigoted hardhat and a runaway hippie involved in the drug scene. It was such a powerful film, that the then-Chicago Censorship Board refused admission to anyone under 18. It drew the battle lines between the working class "silent majority" and an underground movement of anti-establishment activists. Norman Wexler's screenplay copped "Joe's" only nomination.

Speaking of soft-core porn, Russ Meyer, the "King of the Nudies", got big studio support (and money) to create the bloody, sexy and satirical cult classic "Beyond the Valley of the Dolls", scripted by Meyer's friend and Chicago film critic, Roger Ebert! And 1930's movie diva Mae West joined Raquel Welch and John Houston in the abominable guilty pleasure "Myra Breckinridge", in which Rex Reed's female alter ego Myra sets out to destroy Hollywood by first sodomizing a vacuous hunk and then...oh, forget it. Both from 20th-Century Fox.

Incredible.

* * * * * * * * * *

Here are more highlights from some of the more interesting Oscar categories in 1970:

Best Director: Robert Altman had been working in television for over a decade before Fox gave him the task of directing "M*A*S*H*. His method was so freewheeling, that cast members Donald Sutherland and Elliott Gould tried to have him removed from the film, but came around when they saw what he captured on celluloid...

My hero Federico Fellini scored a nomination for the phantasmagorical "Fellini Satyricon", sort of a "Dolce Vita" of ancient Rome, or to paraphrase Fellini, a science fiction film of the past. It was a wallow in color and grotesque imagery and sound, and Fellini's direction was the film's only nomination.....

Ken Russell, with "Women in Love", made perhaps his best film. Known for ever-increasingly eccentric and over-the-top pictures, "Women in Love" showed what I call passionate restraint. It was lush with invention and color and gorgeous set pieces and dead-on performances....

And Arthur Hiller was underappreciated for bringing "Love Story" to the screen, a movie that nailed a portrait of a generation and a new kind of relationship, and moved people, deeply, and with quiet sensitivity, in spite of the sentimental (and Oscar-winning) music score....

All of them lost to Franklin Schaffner for the admirable, conventional triumph of logistics, "Patton".

"Woodstock": a category all its own. This astounding 3-hour Oscar-winning Feature Documentary of the 1969 rock concert nabbed nominations in technical categories usually reserved for fiction films: editing and sound. Editor Thelma Schoonmaker, who would go on to collaborate with Martin Scorsese, shaped hundreds of hours of film into a brilliant amalgam of musical performance, concertgoer interviews, portraits of the promoters and workers, and commentary by the locals. Split-screen has rarely been used so effectively. Scorsese, by the way, was a co-editor on the film.

Screenplay, Adapted: Ring Lardner Jr. won his first writing Oscar in 1942 co-scripting "Woman of the Year" (Hepburn-Tracy). In the 1950's he was blacklisted for refusing to "out" Communist sympathizers and became one of the infamous Hollywood Ten. In 1970, he was back at the winner's podium for his adaptation of Richard Hooker's comic war novel "M*A*S*H". Lardner resented Altman's riffs on the screenplay and willingness to let actors improvise their dialog. He failed to thank Altman in his acceptance speech....

Larry Kramer, who would become an important playwright ("The Normal Heart") and AIDS activist, did an admirable job adapting the impossible-to-adapt D.H. Lawrence novel "Women in Love"......

And George Seaton, who was snubbed in the Director category for "Airport", got a nod here for screenplay, which never met a cliche it didn't love, but still managed to be entertaining. Seaton was an old-guard Hollywood-type, who some might recall directed Natalie Wood in 1947's "Miracle on 34th Street" and Bing Crosby in 1954's "The Country Girl".

Story and Screenplay--Based on Factual Material or material Not Previously Published or Produced:--(In 1970, THAT was the name of what we now call "Original Screenplay"!) Former Brigadier General Frank McCarthy (and film producer) commissioned Roger Corman alumnus Francis Ford Coppola to co-write the eventual Oscar-winning screenplay for "Patton". Coppola would return twice more in the 1970's to accept writing honors for the first 2 "Godfather" films...

Erich Segal was eligible for a nomination in this category because his novel, "Love Story", was not published until after the screenplay was finished. This was one of the first novelizations of a film. The book was one of the biggest sellers of the decade...

Original Song Score: This is a discontinued category, along with Best Adapted Musical Score, which recognized songs from original musicals as well as adaptations of Broadway hits, classical themes, and others. The Beatles took home Oscars for their music from the documentary "Let It Be", a record of the group's final recording session together. This is impossible to find nowadays; I remember seeing this on a VHS rental years ago, and thought it to be a well-made cinema-verite. The win in this category is sort of unusual, probably the Academy's attempt to remedy snubs of the group's work in such classics as "Help" and "Hard Day's Night." (Note the G-rating on the poster!)

Cinematography: Freddie Young scored a hat-trick in his collaboration with David Lean. He followed his previous two wins ("Lawrence of Arabia" and "Doctor Zhivago") with this one for "Ryan's Daughter". Young's work was typically magnificent, although the film was an atypical critical and box-office bomb for Lean, who was so discouraged, that it would be 14 years before he would return to filmmaking (and "A Passage to India".) Although it was about 30 minutes too long, I found "Ryan's Daughter" to be a sweeping and entertaining love story, which used natural landscapes stunningly to symbolize the passion of the young wife of a schoolteacher in 1916 Ireland.

Finally...the Irving Thalberg Award in 1970 went to another hero of mine...Ingmar Bergman.

Next up: Supporting Actor and Actress....which honored two veterans, one of whom had not a word of dialogue in his winning performance.

No comments:

Post a Comment