"Moneyball", the new film about Billy Beane, former baseball player and current General Manager of the Oakland Athletics, who brought his team unexpected success by recruiting undervalued players, is lean and smartly written, and you don't need to be a baseball fan to enjoy it. I can't deny that I had a special level of appreciation, having seen it one day after the final game of the 2011 World Series. The history and romance of the game still flooded my consciousness. That aside, "Moneyball" is compulsively watchable, is surprisingly relevant to the non-baseball world, and is great fun. It is, so far, one of the best films I have seen this year.

The movie combines classic storytelling with a multi-layered character study. "Moneyball" has, at its center, a showcase portrayal of a well-known, behind-the-scenes sports figure and businessman. Many viewers may find, to their surprise, that they will identify with this character's struggles and triumphs. The film covers the period in which Beane, stymied with one of the lowest budgets in Major League Baseball, steals a young business analyst from an opposing team (Jonah Hill in a winning, awkwardly nerdy performance). Together they create computerized statistical formulas to find inexpensive players, whose numbers indicate that they would be able to get on base, with the proper coaching. They recruit these players, find their strengths, and bolster their confidence to get on base and score runs. Mentor and Analyst both struggle against a roomful of old recruiters and a resistant Manager (Phillip Seymour Hoffman in his annoying, bravura best), and begin to see results that win (almost) everyone over to their side.

The film goes deeper, however, without losing sight of the fast-driving plot. "Moneyball" looks at how one man tries to adopt a modern outlook and overcome personal failure; it's a meditation on second chances, and a comic drama about the eternal struggle between traditions and innovations. "Adapt or die!", Pitt (as Beane) states midway through. It's fun to see this character throw his support behind something new and commit to it, occasionally slipping back into sentiment and interpersonal savvy when the new ways don't always provide the right answers.

Beane is particularly invested in the success of a newly recruited down-and-out first baseman, Scott Hatteberg (Chris Pratt). He identifies with Hatteberg's failures, his fears, and his family (both he and Beane are fathers, Beane of a musically talented teenage girl). This thread of the story gives "Moneyball" a warm human appeal. Pratt is very good in a small role that has viewers rooting for him.

"Moneyball" invites the inevitable comparisons to "Bull Durham" (1988). Both are insiders' looks at the quirks, personalities, and unexplainable serendipity that has made baseball survive, almost intact, over the last century. But whereas "Bull Durham" had a sly, almost whimsically romantic center, in which sex is the engine that powers the game, "Moneyball" substitutes sex with technology, and statistics. It's grounded in the sexless reality of business; it's a baseball movie for the Wall Street age.

There is no better metaphor in American movies for tradition, for "the old ways", than baseball, and "Moneyball" lampoons the staid old guys who fiercely guard the game's status quo, like old soldiers. The film also reserves some respect, even affection, for these traditionalists, even as it champions for modern technology as a way to gain a competitive edge.

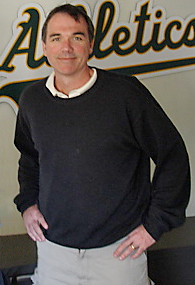

The real-life Billy Beane, a young baseball whiz-kid, saw his own sports career flounder after turning down a college scholarship to play professional ball. The movie handles this in effective flashbacks that convey all we need to know in good cinematic shorthand. As Beane and his protege assemble a dubious roster of has-beens and underperformers for the hapless Oakland team, his instincts prove correct when the team achieves a record-breaking 20-game winning streak, and another shot at the World Series.

Beane turned down a multimillion-dollar offer to manage his dream-team, the Boston Red Sox. In a final irony, Beane's Athletics never achieved a World Championship. Instead, the Red Sox, using Beane's statistical methods, win their first World Series in decades. (Even more ironic, and not mentioned in the film: the Red Sox achieved this under the leadership of Theo Epstein, who was hired when Beane turned the job down, and who is now the President of Baseball Operations for the Chicago Cubs.)

Brad Pitt used to run hot and cold for me. He seemed to pick his roles randomly, and was hit-or-miss. I need not have worried. Pitt is terrific, giving himself over to Beane's portrayal, and getting under your skin, in a performance that is so natural that it might sadly go unnoticed for those year-end pieces of gold.

Pitt has matured well, and this is his most likeable, most nuanced portrayal. He has learned to minimize his facial mannerisms (assisted early on with judicious cutting), and has modulated his voice into a slightly deeper range, delivering his lines with mischief and honesty. Pitt has taken more risks lately, in serious work like "Babel" and "Tree of Life'. He comfortably inhabits a role without trying too hard to hide his persona. He makes his personality work for him, and he is as energetic as he is understated, so that he never seems miscast.

Aaron Sorkin is a puzzle for me. He seems to embrace some values that I generally reject (the glorification of technology, for one), and there is a smugness that wafts through some of his writing that I find off-putting. Is there anything less cinematic than watching movie characters click away at their keyboards? But I have to admit that, even if I find him a wee bit overrated, Sorkin can be a solid writer, and his work in "Moneyball" justifies his reputation as a master of pacing and witty dialogue. He has done marvels with memorable characterizations, too, and packs in a lot of baseball lore, character observation, and history, in a smooth piece of work that inspires creativity from all involved. The script was co-written by Steve Zaillan, whose films in general have failed to impress me (with few exceptions). Sorkin must have provided the wit, and Zaillan the heart, of the screenplay.

Bennett Miller ("Capote") displays a textbook example of strong, "invisible" direction, making every lighting decision, every closeup and character interaction, serve the story and its themes. He is great with actors, too, especially the reptilian Hoffman, in a supporting role as potent as his Truman Capote was gentle. Miller's is the kind of work that I hope will inspire more intelligent young filmmakers to rediscover the emotional and aesthetic pleasures of traditionally good storytelling and careful, layered direction. I hope Bennett, like Pitt, will merit more attention amid the grandstanding of more highly promoted films.

In a movie year filled with superheroes and 3-D, in which destruction has been offered up for our consumption, it is refreshing to spend time with characters who are outcasts, looking for second chances, and who spend their time building something good rather than tearing it down. I will see this movie again.

* * * * * *

(Post-script: There was one jarring note at the end of "Moneyball" that many people will miss, coming as it does over the closing credits. One of the films most charming sequences comes earlier, as Beane's daughter sings an original song, played on a guitar she wants to buy. Over the credits, the song is reprised on a recording she makes for her father, and without warning, there is a refrain, that goes something like "You're Such a Loser, Dad". Was it a joke from daughter to father? was it a downbeat commentary on Beane's inability to finally win that Series? In any case, it doesn't follow. It's a cute song, and can't carry the weight of irony.)

Great review, Tom, really gets under the skin of the different, almost competing elements of the film.

ReplyDeleteI'm definitely going to be seeing this one.

Ben, thanks for the compliment. This was a hard piece to write, actually... to give a sense of the enjoyment I had without overdoing it. There's somethng almost "modest" about this movie that would not stand up to overpraise. I think you'll like the film!

ReplyDelete